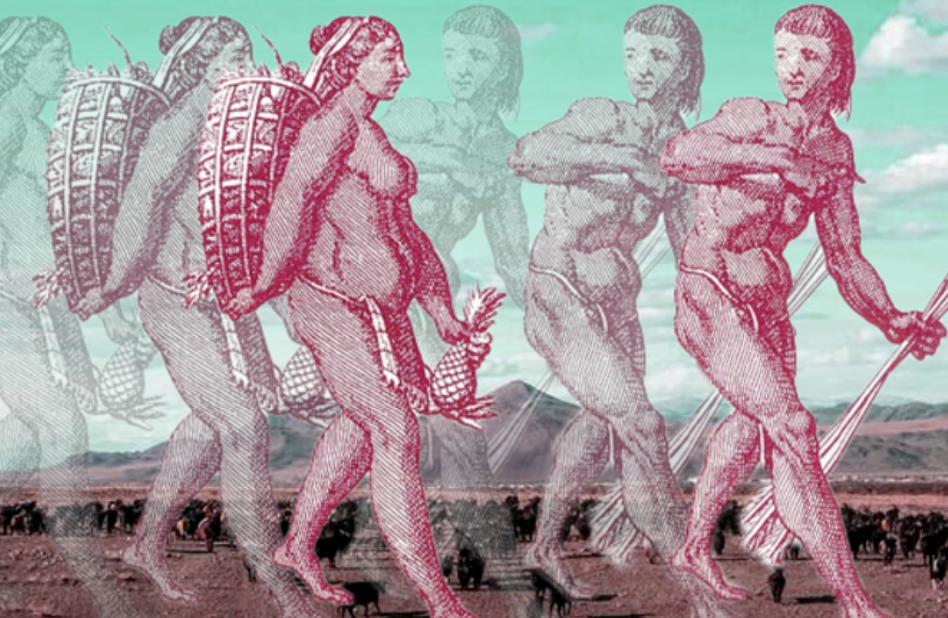

Gender based stereotypes run rampant in many retellings of history. The myth “Man the Hunter,” is one notable example, as many historians have depicted men as hunters, due to the traditionally “masculine” characteristics associated with the activity. In contrast, women have been painted as gatherers who tend to their homes and engage in “feminine” tasks. This notion has established a foundation for gender stereotypes and sexism, and perpetuated the belief that gender roles have been a natural part of society since our creation. In reality, women just haven’t been represented appropriately, viewed as domestic figures, whereas men are considered the breadwinners.

However, the history of hunter-gatherer societies is up in the air completely due to a lack of archival recollection. Whether it be the linguistic discovery of the Rosetta Stone, or the extensive research on hieroglyphics, writing is the primary way historians are able to recollect history. With the absence of writing during the paleolithic time, historians have been forced to draw far-fetched conclusions, providing a large window for inaccuracy. In fact, even the term “prehistoric” suggests a lack of historical context. As a result, from gender roles to even daily life, nothing we know from the prehistoric period is certain: So, if our knowledge of paleolithic societies is severely limited, how did the sexist rhetoric of “Man the Hunter” spread?

As a result, “Man the Hunter” is ultimately a justification in history to preserve the notion of male superiority. For instance in Invisible Women, by Caroline Criado Perez, she writes that in 1966 the University of Chicago held a symposium on primitive hunter gatherer societies called “Man the Hunter.” The consensus of this meeting was that the biology, psychology and customs that made us separate from the apes was a result of hunters being the most influential figures. The rhetoric of “Man the Hunter” was used to justify men as being the most influential figures in human development, diminishing the role of women in paleolithic society. However, Perez writes that hunting as a male activity almost has no baseline evidence. Collections of analysis, specifically from Professor Douglas Bennet from Penn State University have found that paleolithic society may have been matriarchal instead. In fact, in this study he analyzed prehistoric society specifically in the Midwestern United States, determining that there was a heavy matrilinear presence in Chaco Canyon for around 350 years.

These contrasting opinions pose the question as to what sort of society hunter-gatherer looked like. Historians have a few solid theories that debunk the common “Man the Hunter” myth. Findings where women were buried alongside hunting weapons suggested that the hunting was gender neutral, suggest that women were indeed huntersIn fact, women, contrary to public myth, did not hunt weaker game than men, but rather were just as independent,iI 46 percent of the studied societies they took down medium or large game while 48 percent of societies women hunted game of all sizes. Additionally, women often hunted alone, whereas men hunted in pairs in groups. Female tribe members overall were considered the “glue” of the tribe, providing support and game to sustain its members.

Women were also able to break away from the common mold of resource collection, and form an idolized perception of themselves within societies because they were often admired for their ability to keep the tribe alive through reproduction. While sculptures from this time period are scarce, Venus figurines were discovered in the early 20th century, during excavations led by Josef Szombathy, supervised by Hugo Obermaier and Josef Bayer, demonstrating that women were often seen as godlike in the prehistoric period. Venus figurines, shown above, were supernatural and women would keep them in their residences for good luck and fertility. While in the past many scholars have looked at these figures as evidence of female domesticity, recent studies describe them as the perpetuation of female agency and empowerment within paleolithic societies. In fact, Kennett continues to write that in the prehistoric eras, women were able to challenge societal norms that stick with us even today — such as body image. Taking a look at the Venus Figurines, women were idolized for having body types that were curvaceous and voluptuous, because it allowed for successful reproduction and resource collection. A woman’s body was a source of strength, not only domestically as their glass ceiling, but as the breadwinner of societies.

These new findings, while seemingly miniscule, have larger implications for societal gender roles not only between men and women, but also for the gender spectrum as a whole. The repeated rhetoric of many who continue to emphasize traditional gender roles, is to refer back to paleolithic society and prehistoric time periods to demonstrate the gender binary: men and women. However, the gender neutrality and oftentimes even androgyny of nomadic tribes serves as a representation that gender roles are not inherent by nature, but rather developed through society institutionally. A new light on the possibility of a historic matriarchal society may open up new doors for feminism and gender equality once and for all.